In biomass pyrolysis, the energy story begins with its moisture content.

Last week, we discussed how “just dry it more” isn’t a magic bullet for biomass pyrolysis. Many of you shared valuable insights on optimising moisture content (MC), thanks for that. This week, let’s peel back a layer into one aspect of why MC is so critical, how it impacts heat transfer during the drying phase. We’ll go into the others in later posts.

When we heat biomass from room temperature up to around 150°C, it enters the crucial drying phase. This isn’t just simple evaporation; it’s a profound heat transfer event that sets the initial energy balance of your entire pyrolysis process.

Biomass contains different “types” of water:

Free Water: This water, often from direct contact like rain, fills the macroscopic pores and sits on the surface. It’s the easiest to remove, held primarily by water molecules bonding with each other and sometimes by capillary forces within the larger pores.

Tightly Held (Bound) Water: This water is far more stubborn. It’s linked directly to the biomass structure by strong hydrogen bonds with the abundant hydroxyl (-OH) groups found within the polymers. Water can also be held within very small, microscopic pores by strong capillary forces.

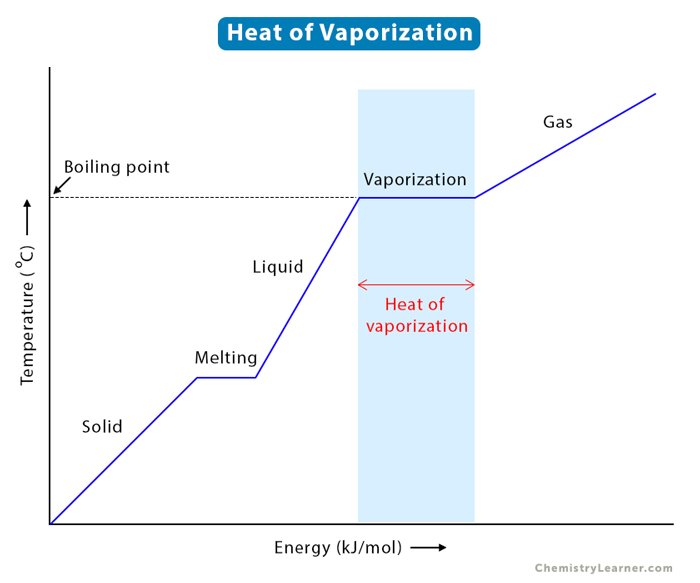

Removing all this water consumes a substantial amount of heat, known as latent heat of vaporization. Until most of this water is gone, the biomass temperature largely remains at a temperature plateau around 100°C. All of the incoming heat energy is being absorbed by the water to break those hydrogen bonds and convert from liquid to vapor. If we have a MC that’s higher than normal the energy-intensive plateau increases, delaying the onset of actual pyrolysis reactions. A MC that’s lower than normal and we increase vapor and solid residence times.

What dictates how much tightly-held water biomass contains? It largely comes down to its chemical composition and the accessibility of those hydroxyl groups:

Hemicellulose: Highly amorphous and rich in accessible hydroxyls, hemicellulose excels at binding water. Biomass high in hemicellulose (e.g., agricultural residues) tends to be more hygroscopic.

Cellulose: Despite abundant hydroxyls, cellulose’s crystalline structure limits external water binding. Amorphous regions still hold significant water.

Lignin: More hydrophobic due to its aromatic structure and fewer accessible hydroxyls. Biomass with higher lignin content (e.g., woody biomass) generally holds less tightly-bound water.

So, a 10% biomass moisture content includes both free and tightly-bound water. Understanding these molecular interactions, capillary forces, and inherent water-holding capacities of different biomass types helps to improve our approach to feedstock management. Effective pyrolysis isn’t just simple drying, but nuanced control of energy and chemistry from the very first stages.

What other “molecular-level” insights have impacted your process optimization? Share your thoughts below!